Smári McCarthy,

member of Pirate Party in the parliament of Iceland,

PPL holder

Translation: Andrei Menshenin

Cover photo: Einar Þór Óttarsson

The board of directors of ferry line Herjólfur recently laid off all employees due to operational difficulties, which can be attributed, among other things, to broken expectations about the number of passengers during the COVID year. Restructuring is underway there, but it is clear that something needs to change to maintain the connection as it should with a tolerable number of trips.

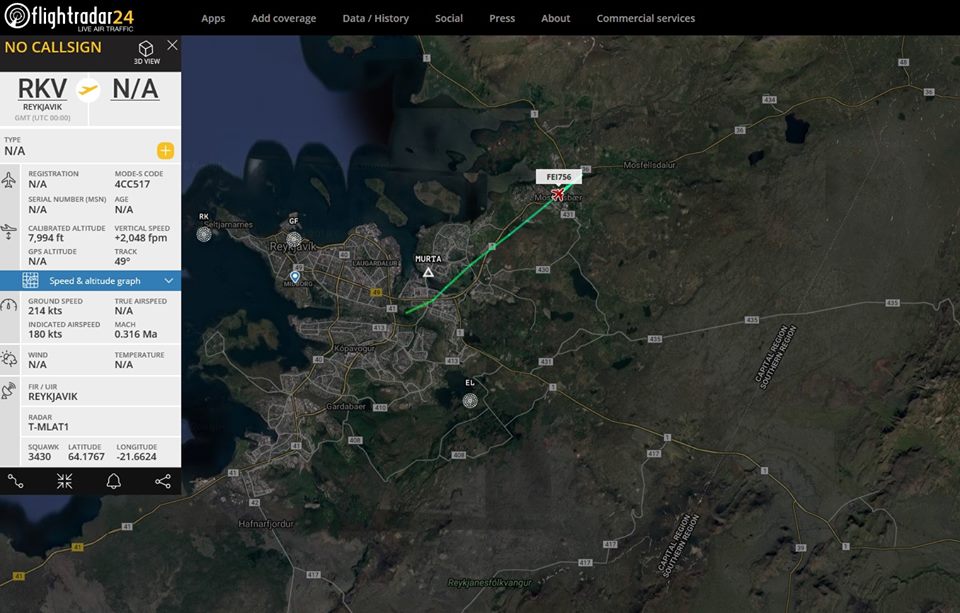

At a similar time, Eagle Air (Flugfélagið Ernir) decided to cancel scheduled flights to the Vestmannaeyjar, simply because the route was unsustainable. There are many reasons for this, especially the reduction in the number of passengers, but also the high operating costs of flights, not least due to the regulatory load. One underlying change was a contraction on other routes. Previously, it was possible to utilize equipment and manpower between those trips.

News is now coming in from Vopnafjörður that the municipal government does not consider it in its interest to take over the operation of the airport there, as has been done, for example, in Þórshöfn. This is an understandable position, but when combined with the other news, there is reason to wonder how the form of operation would best ensure transport in rural areas.

The need to travel

Technology gives and technology takes. Telecommunications at the speed of light around the world have reduced letter mail, which cuts into the revenue streams of postal companies as well as mail carriers. This may sound like a segue, but keep in mind that in many parts of the world, postal services financed the development of transport infrastructure, and in Iceland, there are literally dozens of airports all over the country that had little other purposes than to ensure mail and freight transport at a time when the highway system was worse.

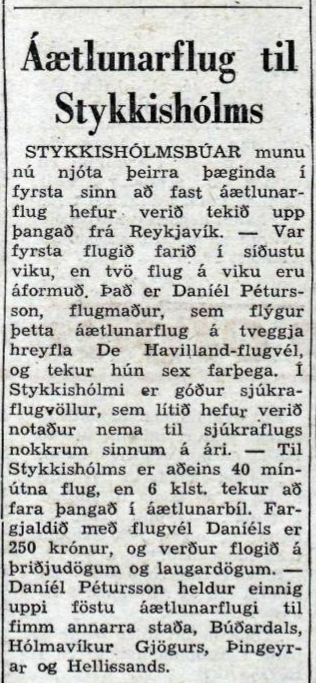

Improved highways have also significantly reduced the demand for flights, as for example there is no longer a 6-hour journey by a coach from Stykkishólmur to Reykjavík, as there was in 1961. At the same time, there is less need for scheduled flights to Hellissand, Búðardalur, Sauðárkrókur and Raufarhöfn, as it was here years before.

The need to travel has not changed and even increased. But the modes of transport have evolved significantly, not least now that it is possible to “attend” meetings all over the world via the internet.

The development of highways and telecommunications is one of the reasons why technology has taken air transport from many parts of the country. It has become cheaper for each and every passenger to drive for just over 2 hours between Reykjavík and Stykkishólmur than to fly for about 30 minutes in between. The issue seems to be resolved in the same way, mainly due to the small number of passengers, when looking at an example of a woman who has to get from a meeting in Þórshöfn to another meeting in Bíldudalur. She does not plan a 10-hour drive but is likely to stop for one night at Krókur and even organize meetings each week. Direct flight device just over 2 hours. Scheduled flights through Reykjavík would cost tens of thousands more, would include three airlines (Norlandair, Air Iceland Connect, and Eagle Air), and would take no less time than driving due to waiting at airports. This is not an imaginary example, although it may be a rare path.

The real question arises (to which the title of this column refers): is it possible to increase the macroeconomic efficiency of transport by changing the form of operation?

Possibly. But to talk about it, we only need to talk about Alexandersflugvöllur airport, only about Herjólf, and only about licensing.

The contradiction in the transportation plan

Road 749, Flugvallarvegur in Sauðárkrókur, is one of the many roads that appear in the basic network of the Transport Plan. This means that it must be subject to a maintenance plan like other roads in the basic network, funded by the Treasury. This in itself would be perfectly normal, except that according to the same transport plan that road does not lie anywhere. This is because Flugvallarvegur connects Sauðárkróksbraut and Alexandersflugvöllur airport. However, Alexandersflugvöllur airport is nowhere to be found in the transportation plan.

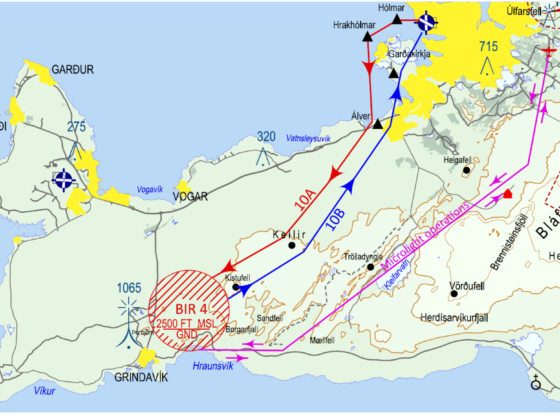

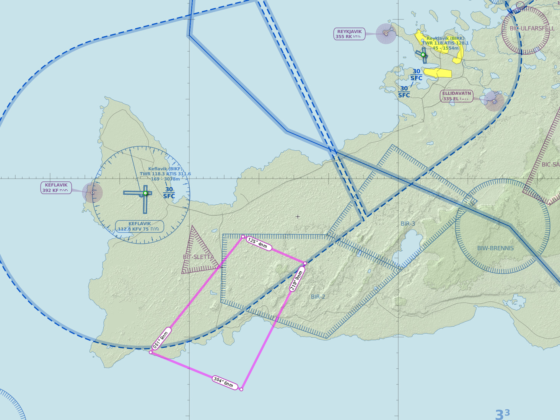

Airports in the main network of the transport plan are Keflavík, Reykjavík, Bíldudalur, Ísafjörður, Gjögur, Akureyri, Grímsey, Húsavík, Vopnafjörður, Egilsstaðir, Höfn in Hornafjörður, Vestmannaeyjar and Þórshöfn. And even though Alexandersflugvöllur is mentioned as a part of the main network in the Icelandic Aeronautical Information Publication (AIP), which is published by national airport operator Ísavia, the airport is not in the transport plan, despite it is a long route and fully suitable for scheduled flights if there is interest.

In addition, the Aviation Handbook contains countless landing spots, even though less than half of all landing spots in the country. For example, Skálavatn and Nýjadalur can be found on the list of registered landing sites, but neither Bolungarvík nor Hvolsvöllur. The reasons are many and in fact quite a discipline in themselves, but a certain truth remains: the sound and the image do not go together in the transport plan, as the plan does not even properly list the existing transport structures. From there, she creates a real plan for how things should work.

It must not be the responsibility of people who do not know what to do to create such a plan. If the country’s transport is to be socially efficient, the plan must be based on more than a simple cost estimate.

The local community

In some respects, the same reason lies behind the under-registration at Alexandersflugvöllur and the islanders’ dissatisfaction with the fact that Herjólfur’s operations were carried out through a company in Reykjavík. People who are unfamiliar with local customs have a distorted view of the realities there. If you ask a person in Reykjavik downtown on Laugavegur street, he would be forgiven for not understanding why it is important to maintain air transport to somewhere like Gjögur. Probably he even will have difficulties finding Gjögur on a map. But for the people who live in the area, this is the difference between being able to live there and not being able to.

Likewise, the clear and simple premise of settlements in the Vestmannaeyjar is that Herjólfur ferry makes several trips a day, not only with passengers but also goods and supplies. And it is no less a prerequisite for settlements that it is possible to get to Reykjavík by air, as there is a fundamental difference between a 22-minute scheduled flight each way and a 3-hour drive and boat trip when the goal is to attend a short doctor’s visit ─ which is not always possible.

There are other reactions to this that the man on Laugavegur would possibly be forgiven for: some people do not feel that it “pays off” to live outside Reykjavík and say that poor transport is a sacrifice for those who decide to live in the countryside, in the same way as traffic jams and pollution is the sacrificial cost of those who decide to live in Reykjavík.

There is no need to waste a lot of words on how stupid that attitude is, as it must be perfectly normal for people to have both the freedom to choose a place to live according to their criteria, and the freedom to fight for better living conditions in that place. It applies everywhere. And to the extent that the purpose of society is to improve the living conditions of all, one may ask whether it is not a good idea to base services in each area at least to some extent on the knowledge of those who are familiar with local customs.

Herjólfur’s operation in the hands of the Islanders is better than Herjólfur’s operation in the hands of people who never go to the Vestmannaeyjar. The organization of airport affairs is also possibly better in the hands of local people. But something costs this.

Dispose of regulations and hide costs

Most people should be able to agree on the merits of having good principles that ensure safety and well-being, prevent disputes, and foster fairness. But after excess comes poverty; in this case literally.

Although joining EASA (European Aviation Safety Agency) and participating in other European co-operation through the EEA has given us a lot, there are many examples of Icelanders’ implementation of the rules being based on a limited understanding of the nature and purpose of the rules and especially burdensome implementations. and possible for those who have to follow the rules, but as ineffective as possible for those who have to enforce them.

This fraudulent way involves considerable hidden costs for society. The emphasis on the “Scottish Way” is based on the same premise, a misunderstanding of the nature of the problem. Promising people a refund from the state if they pay for a flight does little more than increasing how much people can pay for airline tickets. It does nothing to increase seat availability, route selection, or reduce airline operators’ operating costs. The Scottish route is approaching the problem from the wrong end, and in the case of the Vestmannaeyjar has in fact made flights more expensive ─ and later unavailable ─ before the Scottish route itself took effect!

To repeat: societal efficiency cannot be achieved simply by looking at a simple cost estimate. It is necessary to take into account the mounting opportunity costs of the rules being wrong, overly burdensome and that transport is cut off, and even the local authorities with them. This is not a project for Excel, this is a large and complex system that needs to be identified as such.

How do we solve this example?

Let’s start by acknowledging that the Isavia experiment has not been successful for Icelanders. It was rightly noted that the main political goal of the establishment of Ísavia was that the country’s political elite could blame someone else when things went awry. Instead of having a company that runs a shopping center well, air traffic services differently and airports poorly, it would be better to move the operation more to the locals in each place, but not to the municipalities with associated costs and probably low income as is customary for the state.

Thus, it would possibly be best to rebuild the Civil Aviation Administration, but let it operate distributed throughout the country with a joint planning unit for coordination to ensure professional knowledge and speed up the processing of problems. This apparatus would remove the gap between Ísavia and the Ministry of Transport and create political responsibility for the issue again. Funding could come from the state treasury to replace landing, parking and air navigation charges, which significantly reduce the possibility of having scheduled air connections.

We also recognize that the operation of ferries is better in the hands of local people, but that it needs normal support for such operations. The upheaval in Herjólfur’s operations is certainly a result of COVID, who may have to accept this as a financial blow this year, but in the future, the state’s support must be more flexible in accordance with the state’s volatility equalization role.

But in general, the country’s transport needs to be rethought in a way that is tailored to the needs of all settlements, makes better use of all options, and does not create unreasonable barriers on the basis of rules that hardly apply.